CERN Hack days, September 2013 and February + March 2019

CERN is a Casino! … for Physics … Wanted to be a little dramatic at the beginning of the article and could not think of a better form of entry than that :)

On a more serious note, CERN houses the largest and most complicated Scientific experiment ever carried out by human beings. Someone else had likened CERN to an airport and the analogy also fits quite well with what goes on at the facility. CERN avails infrastructure to carry out high-energy Particle Physics experiments (non-commercial flights). The equipment researchers find at the lab are comparable to runways, air-traffic control systems, ground staff, tight security equipment & procedures, hangars, landing rights and so on. Experiments conducted are at energy levels that are not attainable yet in other laboratories around the globe.

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a 27 KMs circular tunnel dug 100 metres deep below ground. Inside it, protons stripped away from hydrogen nuclei are accelerated at close to the speed of light. The actual figure is 99.99999896% of light speed (0.9999999896 * c). Once in a while, the beams have their paths crossed over while traveling in opposite directions. A collision occurs at an average rate of 40 - 60 million times every second. At such speeds, each proton beam can make 11,000 revolutions around the LHC tunnel every second. The energy produced by such activities is so intense that tiny points heat up to be hotter than the core of our Sun. In effect, they become the hottest points in the observable Universe. At the same time, new particles come into existence. For those few fractions of a second that elementary particles come into existence, Physicists can catch a glimpse of what the Cosmos looked like moments after it began to rapidly expand and cool down. This phase in the life of the early Universe is now referred as the “Inflation” period.

These searches are necessary due to the fact that there were durations when the early Universe was not transparent to light. Telescopes can only observe so far back into the past, excluding about the first 380,000 years of the life of the universe. In reality, the universe became oblique again and it took between 100 and 380 million years for the oldest stars to form. A combined half a billion years passed before light from those early stars started to shine through empty space without any interruptons. The primary goal of these types of probes is to acquire an understanding of the most fundamental Laws of Nature.

It is these kinds of simulations into origins of Time that prompted the creation of the distributed hypertext / World Wide Web system at CERN. A lot of data gets collected by giant detectors at collision points run and maintained by various experiments (ATLAS, CMS, ALICE, LHC-b and TOTEM). This is kept for later analysis by disparate Scientific collaborations running those experiments. The collaborations consist of at least 17,500 individual Scientists and Engineers. Their nationalities span more than 70 countries. That fast became a source of regular frustration for the organization to keep track of what was going on and when / where / by who. The inventor of the document Web, Sir. Tim Berners-Lee, decided to focus on this problem and do something about it. It was reported later that CERN only hoped to change the way it works internally with the new tool that they had created. They ended up changing the rest of the world for good.

Fast forward to 2013 AD, approximately 13.8 billion Earth years after the Universe had started to expand …

I had been living in Kenya, one of the countries that make up East Africa’s region, since birth for a little over 30 years. For two years before 2013, I got involved in the organizing of a Science event known as “Science hack day” in Nairobi, the country’s capital city. Science hack day aims to bring together scientists, artists, developers, designers, mathematicians, musicians, engineers, writers plus all sorts of awesome people into the same physical space. This is for a duration of 48 hours, a period of time that they could build even more amazing stuff together.

I had seen a tweet making an announcement that the free and open Web had been in existence for the past 25 years. It called for a celebration of sorts. I was thrilled at the news and decided to leave a comment using an e-mail contact placed at the bottom of a linked page. I wrote a message to CERN’s Web team expressing excitement for, and wishing them good fortune in their efforts aimed at restoring the website of the first Web server. I also mentioned what I did to earn a living (Computer Programming) as per the request on the post. I must have been the first person to write and got a response from CERN a few minutes later sounding bubbly about my feedback to their (We)b-log post. The writer got in touch afterwards making a polite encouragement to me to hand in an application to participate in a project to restore the Universal Line-mode browser (LMB). LMB was the second free browser authored by a Mathematics intern at CERN, Nicola Pellow, from 1990 to 1993. That was on the first week of June 2013 and it was one of the highlights of my year, a peak in my natural life too.

A month later in July 2013, another communication was made via an e-mail message by the Web manager at CERN congratulating me. It was for being one of a handful of people who had been selected to take part in a Hack day at CERN in September 2013. The goal was a restoration of the website of the first Web server and parts of the first Web server’s environment. That piece of news was so unbelievable to me. For the next two months, I checked up the web page with the list of participants with much skeptism each morning before leaving bed. I was looking for confirmation if my name had been stricken-off from it. That would hopefully be followed by an apology from CERN. An explanation that there had been a random “clerical error” made in the whole selection and announcement stages of the project was enough. I kid you not!

I showed up in September 19th - 20th 2013 after going through the whole Schengen VISA application process at the Swiss embassy in Nairobi. It was intimidating to be in the presence of such incredibly talented Web designers and developers from all over the world. A sense of “impostor syndrome” consumed me. Saying that I felt wildly out of place would be a gross understatement of my sentiments during the hackathon. My task was to carry out research into parts of the Web’s early history and eventually publish the content into a story-telling website. That would go with the Universal Line-mode browser’s emulator release which got built in two days of Web development by the rest of the team. The final output was quite decent and is available for the public.

CERN hack days 2019

This time I was in Canada and had completed graduate studies at the University of Alberta. My research group was at the university’s Simulations and Modeling laboratory for Construction Engineering and Management practices. I worked under the kind supervision of Dr. Simaan AbouRizk from January 2016 to May 2018.

CERN’s intention was to rebuild the first Web browser ever. This original browser served as a prototype to the current distributed hypertext system that had been written by Sir. Tim Berners-Lee in about four months on a NeXT Cube machine from March 1989. The people concerned with planning of the project - - CERN & society foundation with the U.S mission in Geneva - - had figured out that it would be far simpler to reunite the Universal line-mode browser’s emulator team back at CERN. They would perform similar tasks like they did on the previous occassion. I jumped fast at the opportunity. This time I felt more confident about my ability to contribute to the project as compared to our previous visit. Also, the invitation was for a longer period of five days. It was over the Valentine’s day week. To me that symbolized a gift of love and appreciation from the entire Scientific and Technology community!! As usual, we were given one task and left with absolute discretion on how to go about it.

Most of us performed similar tasks to what we engaged in during the 2013 visit. My role was to work on the story-telling website again. I got to write some bit of mark-down “code” for the static site generator we were using for the project, Eleventy. I also helped out in connecting to the replica of the NeXT Cube computer that had been borrowed from the Science museum at Laussane for us to work with. The link was over a wired ethernet network. Kimberly Blessing and I managed to get a copy of an earlier version of the WorldWideWeb browser from a copy of Sir. Tim Berners-Lee’s hard drive preserved on a Compact Disc. I had to install a light-weight ftp (File Transfer Protocol) server software on my laptop first. Then I connected the NeXT Cube to the network and assigned both the NeXT Cube and my laptop static I.P (Internet Protocol) addresses inside CERN’s local area network. After that we transferred compressed WorldWideWeb setup / UNIX binary files earlier copied to my machine to the NeXT Cube for installation.

Our day started off with us watching a video of someone who had a running copy of the WorldWideWeb browser on an actual NeXT Cube machine. This was while giving a walk-through of the process from boot-up to shutdown. We also got to talk to and work with some of the Web pioneers, Jean-François Groff and Robert Cailliau. Some other highlights from our stay include;

- A visit to a restaurant downtown to eat the best Swiss fondeu besides lake Geneva.

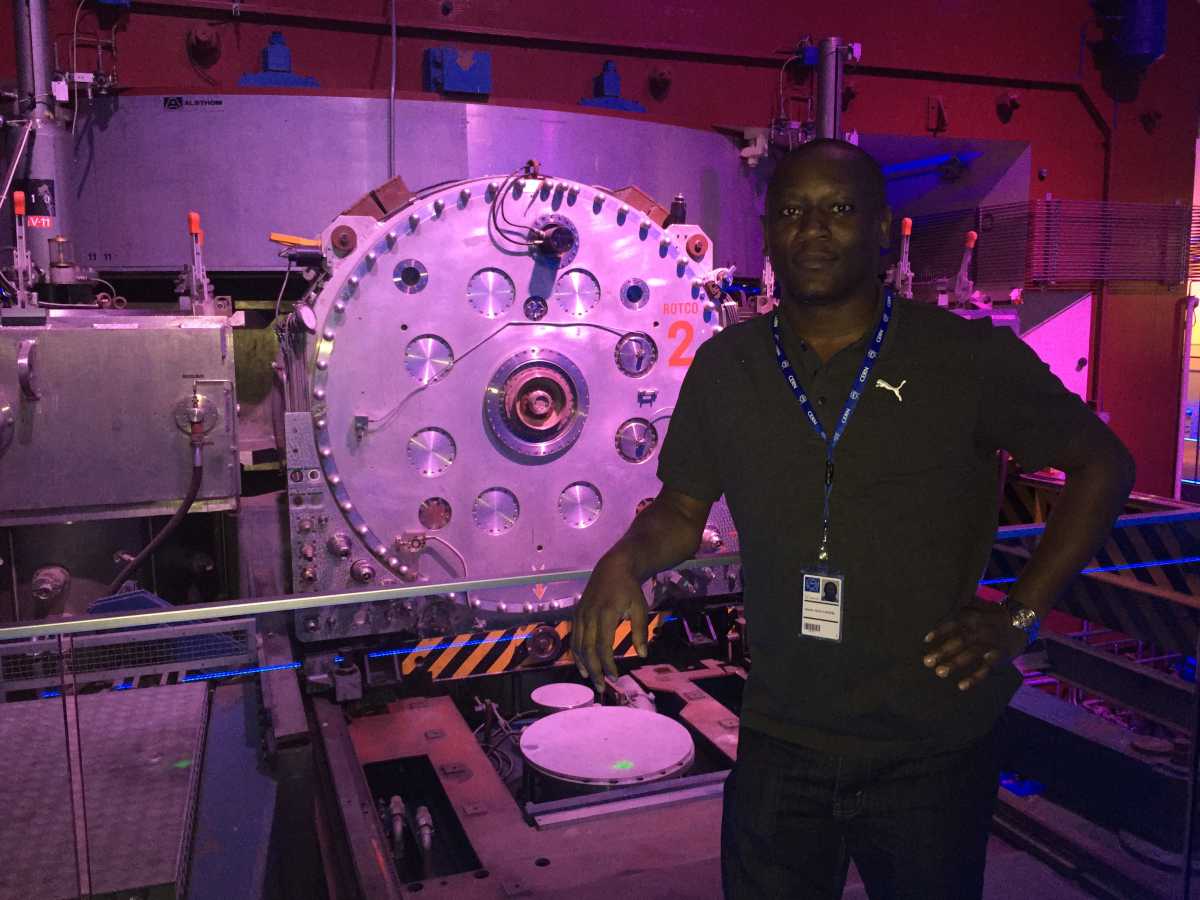

- A guided tour by Dr. James Gillies of the SynchroCyclotron (SC). SC is the oldest accelerator at CERN dated 1957, now the star of a cool projection show for CERN’s visitors.

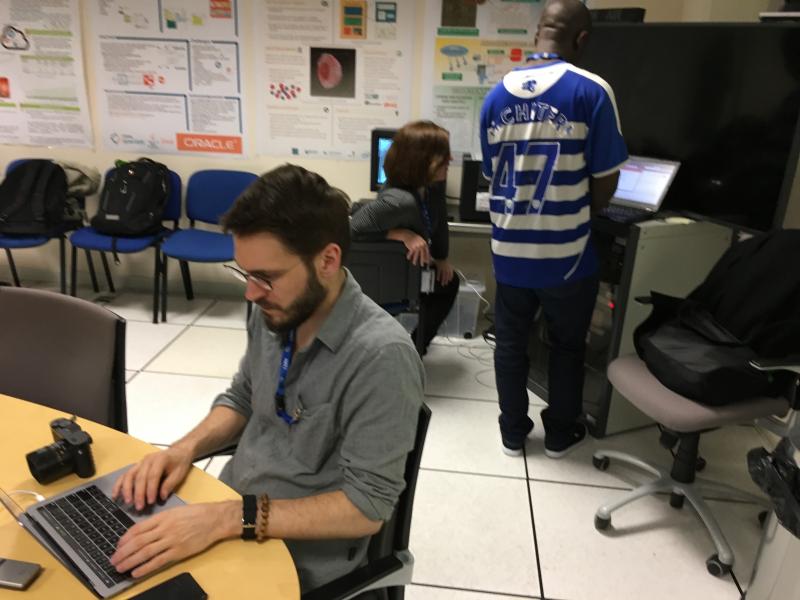

- We also did all our coding from CERN’s main computer room. We had a breath-taking visit to its high perfomance computing grid. The grid collects data produced by all Physics experiments when the LHC is operational.

- Last but not least, we had a brief tour of the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR) experiment after completing our project at the end of the week’s hackathon.

Web@30 celebrations #ForTheWeb

This event occured on the 12th of March 2019 to mark 30 years from the time that the original proposal for the World Wide Web system was authored by Sir. Tim Berners-Lee. It was a colourful day attended by pioneers of the Web technology and leading thinkers in the field. The host was CERN’s current director general, Fabiola Gianotti. The guest of honour, Sir. Tim Berners-Lee and his close collaborators from the early days expressed disappointment with the current state of the system. They urged participants from all over the world to consider the original intentions of his invention. With that they can work towards restoring the technology to its ideal state. The Web had its initial design as being decentralized, free of surveillance and exploitation neither for-profit nor for political power. It was collaborative, had real privacy and was beneficial to all people regardless of physical location and status in society.

In summary

Physcisits get to peek at early conditions of the Universe. In a similar way, we engaged in a “Digital archaeology” exercise at the same laboratory where the Web technology came from 30 years ago. We recreated an experience of the World Wide Web system as what it was at its birth for many people who did not have the opportunity to do so first hand. For many of us, that is a revealing experience. Many people can see how such a simplistic (now) piece of technology has had a profound impact on many spheres of our lives as human beings. The Web will continue to do so well into the foreseeable future.